Designing human evaluations and reporting the outcomes

Published:

Every once in a while, there is an MT paper claiming to have achieved human parity (e.g. Hassan et al., 2018, Popel et al., 2020). To be fair, a message like

Our system is as good as human translators

would be ridiculous and is not what people actually claim. What they do say in papers is

Assuming a particular design of human evaluation that is used widely in MT research, for a particular language pair , for a particular domain of text, a statistical analysis shows that it is quite likely that our system is on par with the particular way human translators produced our test material.

In short, many things are “particular” about a claim for human parity! When it comes to human evaluation — like automatic evaluation — the devil is in the details. Some details are quite straightforward: claims are limited to the language pairs tested, and to the kinds of text that are tested.

What is less obvious is that it matters greatly for human evaluation how humans are shown the material to be evaluated, which decisions they have to take or if they are professional translators.

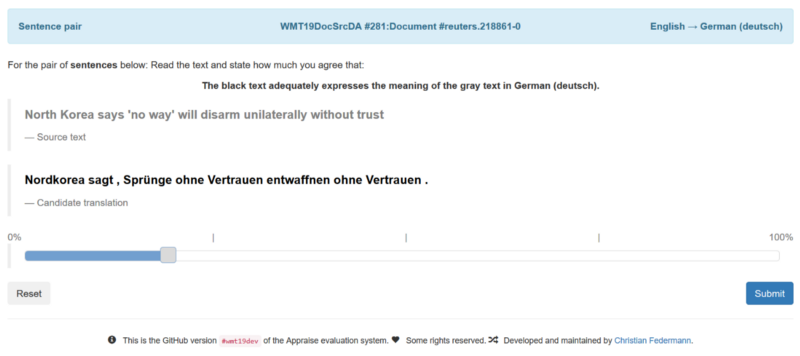

How are humans shown what they have to evaluate? As an example, for the human evaluation of the WMT19 News Translation Task the default evaluation interface looked like this:

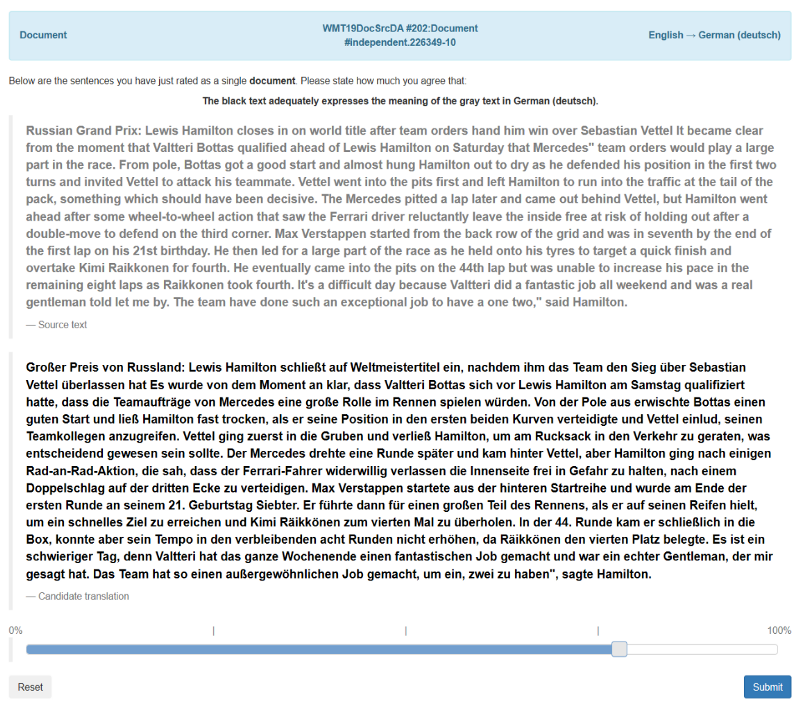

So, this evaluation shows translations sentence-by-sentence. But then there are also language pairs for which a document-level evaluation was performed:

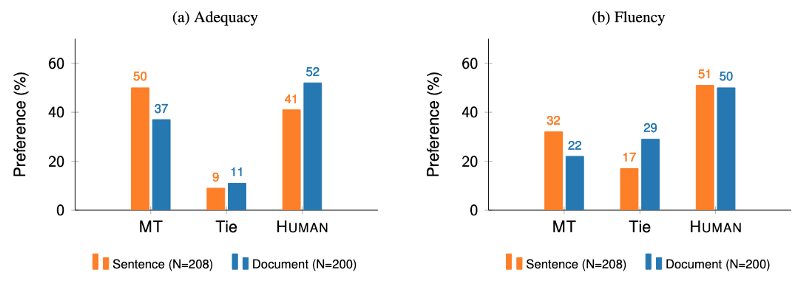

Why also have this document-level evaluation? Läubli et al. (2018) found that while it was true that humans had no preference for human translation over MT output if they evaluate on segment-level, they clearly prefer human translation in a document-level evaluation:

Other works by, among other people, my colleague Samuel Läubli, Sheila Castilho and Antonio Toral have identified many other factors that impact human evaluation, such as:

- Läubli et al. (2020) found that it matters whether the humans doing the evaluation are professional translators or just lay people. For WMT, the people doing the evaluation have been mostly researchers or bilingual crowd workers in the past.

- Läubli et al. (2020) also found that it matters how the human references used in the evaluation are produced. The translations for WMT test sets are created from scratch every year, WMT commissions them from LSPs. For a particular language pair, this means that either the source or target text is original, while the other side is translated. Evaluating already-translated text (“Translationese”) is different from evaluating original text.

- Castilho (2020) found that it is hard for humans to assign a single score to an entire translated document, and that the inter-annotator agreement of such scores is quite low compared to a sentence-level evaluation.

There are many more such interesting observations that are worth studying in detail if you are planning a costly human evaluation. In my view, WMT is taking those studies quite seriously and is trying to improve the human evaluation setup every year. For instance, WMT 2019 already had a pilot for document-level evaluation that was improved this year and WMT 2020 took great care to take into account the directionality of the human references.

Going forward, I think it will especially be important to learn more about document-level human evaluation. At the moment we know very little about the impact of various design decisions (Castilho, 2020) and our current method of collecting document-level judgements seems inefficient (Mathur et al., 2020). Establishing clear protocols for document-level evaluation will enable better research on document-level MT systems.

Recommendation

When designing your human evaluation, follow current best practices, for instance the ones laid out in Läubli et al. (2020). Be aware of the limitations of your experimental setup and adjust claims accordingly.