Computing and reporting BLEU scores

Published:

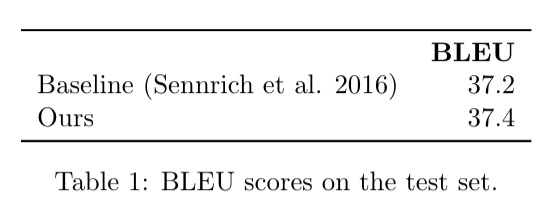

BLEU scores are ubiquitous in MT research and they usually appear in tables that look like this:

Now, can we conclude from this table that the system proposed by the authors beats Sennrich et al.? The only right answer is: impossible to know without more information.

Not all BLEU scores are created equal. There are plenty of ways in which the authors could have arrived at a seemingly innocent final BLEU score of 37.4. In this post, we will explore some of the reasons for this.

There are various ways in which BLEU scores can be computed, and ways to choose the exact inputs used for this computation. Before we dive into this let me introduce some helpful terminology:

Hypothesis: Translation produced by an MT system, as a string

Reference: Gold-standard, in most cases human translation, as a string

BLEU is a corpus-level metric: it requires the entire test corpus at once. Still, corpora must be segmented into individual sentences. Another way of saying this is that tools that compute BLEU take as inputs a list of hypothesis sentences, and a corresponding list of reference sentences.

Since BLEU internally collects ngram statistics, it is obvious that a hypothesis or reference string should be tokenized or segmented (depending on the language). To understand why, consider the following example:

Hypothesis: A cat sat on the mat.

If we were to collect ngrams from this sentence without tokenization, then (the, mat.) (with a .) would be one of the bigrams. That would clearly be unintended. Given that tokenization is required, it is only natural to ask questions such as:

- My preprocessing pipeline tokenizes the training data. Consequently, the MT output is already tokenized. So, I just compute BLEU using this already-tokenized MT output as hypothesis, and also tokenize the reference with my tokenizer?

- My data is not tokenized at all, hence my MT output is not tokenized. So, I just take the very best tokenized for the target language used in my experiments, and use it to tokenize the hypothesis and reference?

The answer to both of those is: no! That would by no means be the correct way to compute a BLEU score. The problem with both is that a custom tokenizer is used instead of a standardized one. Using your own tokenizer means forgoing the comparability of BLEU. Since comparability is an important raison d’être for an evaluation metric, this defeats its purpose to a certain extent (you can still use those scores to compare your own models internally). Also, it makes reproducing your BLEU scores much harder for other people, since they need access to your tokenizer or detailed information about it.

Taking this a step further, if you think that

Certainly to compute BLEU scores the very best, most accurate tokenizer for a particular language should be used?

You are doing yourself a huge disservice. The main goal of computing BLEU scores is not accurate tokenization, but automatic MT evaluation that correlates well with human judgement. It is not necessarily true that the best language-specific tokenization leads to the best agreement with humans. On the very same grounds you could argue that the fastest person on earth must be the most good-looking.

And even if that were true, language-specific tokenization would still need to be standardized to meet both all-important goals of automatic evaluation: comparability and reproducibility. For some particular languages, the tokenization in SacreBLEU is indeed different from the standardized, language-independent mteval-v13a tokenization. For Japanese, for instance, MeCab is used instead. This works because using MeCab tokenization for Japanese is not an ad-hoc, per-experiment decision, but implemented in a standard evaluation tool.

Speaking of SacreBLEU – it is a tool written by Matt Post that computes BLEU scores correctly and provides a signature that can be pasted into papers (Post, 2018). As I am writing this post, the list of SacreBLEU features is growing. For instance, the tool now also downloads standard testsets (think: benchmarks), has useful tokenization for most languages and CHRF and TER as alternative metrics. Other people have contributed to SacreBLEU development as well, such as Ozan Caglayan and Martin Popel who help maintain the Github repo.

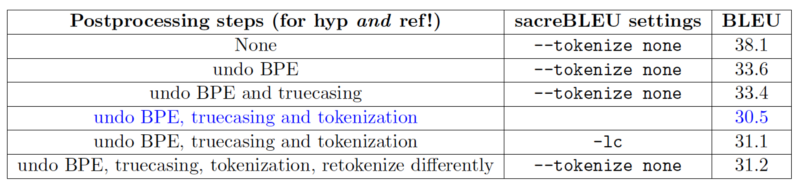

On a side note, using different tokenizers and other postprocessing decisions can cause a larger-than-most-people-think difference in BLEU. Here is an example from coursework (for the MT course I taught with Rico Sennrich). The basic assumption is that the data for training is tokenized, truecased and then segmented with BPE. Of course then the test data needs to be preprocessed in the same way, but you can postprocess translations in a number of ways, as long as you are consistent between hypothesis and reference. The outcomes can be quite surprising:

Some observations from the table above:

- If you compute BLEU on BPE-segmented text (first row), this gives a very high BLEU score. This is likely because smaller units (parts of words) are more likely to also appear in the reference.

- If you evaluate on tokenized text and turn off SacreBLEU’s internal tokenization (third row, wrong), the BLEU score is about 3 points higher than if you detokenize your translations and let SacreBLEU do its standard tokenization internally (fourth row, correct).

- If you compute a non-standard BLEU score that is not case-sensitive (fifth row, wrong) this also increases your BLEU by 1.

- Finally, if you detokenize, then retokenize with a trivial third tokenizer that is neither a) your own ultra-good, language-specific tokenizer nor SacreBLEU’s internal one (last row, wrong), this also changes the BLEU score by more than what many people report as a significant difference in research papers!

It is quite impossible to overstate the significance of those observations.

Essentially, you should think of tokenization and related pre- and postprocessing steps as being internal to your translation system. Think of evaluation as an end user of your system, to whom you would never show tokenized intermediate outputs, or even explain that there is tokenization.

Outside machine translation, there seems to be even more confusion about BLEU as an evaluation metric, for instance because people in summarization or other NLG research compute it with different maximum ngram sizes. Also, for anything other than machine translation, BLEU is routinely found not to be reliable at all as an evaluation metric.

SacreBLEU is currently the de-facto standard for computing and reporting BLEU scores. If you are the author of a paper and intend to show BLEU results, I recommend that you use SacreBLEU. If you are reviewing a paper that a) uses a now-deprecated tool such as multi-bleu.perl from Moses or b) does not clarify how and on which data exactly BLEU scores were computed, point this out in your review.

Little-known fact: the SacreBLEU paper was initially rejected from ACL – which Matt Post was grumpy about for a short while. On the plus side, the poster used for the WMT session where it was eventually accepted was a rarely-seen hand-drawn comic strip!

Recommendation

When reporting BLEU scores, compute with translations that are fully postprocessed, and pristine references that have not been tampered with at all. Leave tokenization to the standardized BLEU tool.

FAQ

Q: There is also the sentence-bleu metric which works on sentence level instead of corpus level?

A: BLEU is really only defined at the corpus level. For an individual sentence, BLEU is very often 0.0 , because none of the higher-order ngrams are also in the reference sentence. There are smoothed variants of BLEU to avoid this (Chen and Cherry, 2014). However, those smoothing techniques introduce subtle biases that may be hard to notice (e.g. Nakov et al., 2012).

Q: Why still explain the correct use of BLEU when it is very old and does not correlate well with human judgements anyway?

A: It is not true that other, newer metrics outperform BLEU consistently when it comes to system-level correlation with human judgement. For instance, one of key messages of the WMT 2020 Metrics Task is that for translation to English, there is no compelling evidence that any metric outperforms BLEU in a consistent manner.

However, the metrics task also showed that BLEU is really bad at telling the difference between high-quality MT outputs and high-quality human translations. Embedding-based metrics such as COMET (Rei et al., 2020) appear to have a distinct advantage here.

Q: The default tokenizer in SacreBLEU is basically useless for my target language. What can I do?

A: If there is a tokenizer elsewhere, you could try and contribute it to SacreBLEU. That would help with standardized evaluation for this language in the future. If there is no tokenization at all (as is the case for many languages), a character-based evaluation metric would be a viable alternative to BLEU. I would recommend using CHRF(++) (Popovic, 2017).